n the 1980s, Cypriot football had already reached its fifth decade, yet its main protagonists—the players—could still be described as being at the bottom of the hierarchy. The challenges they faced were numerous. They were not allowed to leave the teams with which they had signed contracts as teenagers. They had no insurance. They played on public holidays, were paid little, and, most importantly, had no say in matters that directly concerned them.

The creation of an organized body was, therefore, the only way forward to improve the working conditions of footballers. This is how the Pancyprian Footballers’ Association (PASP) was established.

The foundations for PASP’s formation were gradually laid with the help of journalists who wrote about the need for players to organize. “We wrote that footballers needed to form a union, to fight for their rights. To claim fair pay, medical care, and insurance. Eventually, we gathered enough players and got started. I’m proud to have been among those who helped create the Association,” recalls journalist Petros Chatzichristodoulou.

As expected, the players’ decision to unionize was not well received by the Cyprus Football Association and the clubs. “The contribution of lawyer and later judge Alekos Panayiotou to the legal side was significant. I had advised them to elect a retired player as PASP’s president—someone who could not be pressured by those in power,” notes Chatzichristodoulou. The first president elected was Yiannakis Yiangoudakis, who, while not a retired player, was particularly active.

Πρώην Προέδροι

Yiannakis Yiagkoudakis (1987 - 1991)

“For many years, whenever we gathered with the national team, we would talk among ourselves about the need to get organized. Eventually, I took the initiative, and together with five or six other players, like Giannos Ioannou, Petsas, Evagoras, Thrasos, Floros, and with lawyer Alekos Panayiotou, we made a big effort. We gathered 450 Cypriot players at the Miramare Hotel in 1987. We told them it was time to claim our rights, and we elected the first committee, where I became president.

It was difficult at first because we had to convince the players. I remember that, at seminars we organized, we would send players from APOEL or Apollon to clubs labeled as ‘left-wing’ to show that politics didn’t divide us. We even set the membership fee at one pound per year to cover our expenses.”

The first PASP board was housed in the then offices of the Cyprus Olympic Committee, located on a side street off Griva Digeni Avenue in Nicosia. That’s where the effort began to address the problems footballers were facing. “We went to the CFA with reasonable requests. We asked, for example, to establish a transfer window in December. We requested insurance, and that games not be played only on Sundays, but also on Saturdays. We raised concerns about military service. In general, we received negative responses. So, we decided to go on strike.

But because I knew there was a real risk of being divided, I secretly went to the head of the referees and asked him that when we announced the strike, they would also declare they wouldn’t go to the stadiums since the players were striking. That strategy worked. We showed our determination, and eventually, the CFA invited us for talks.”

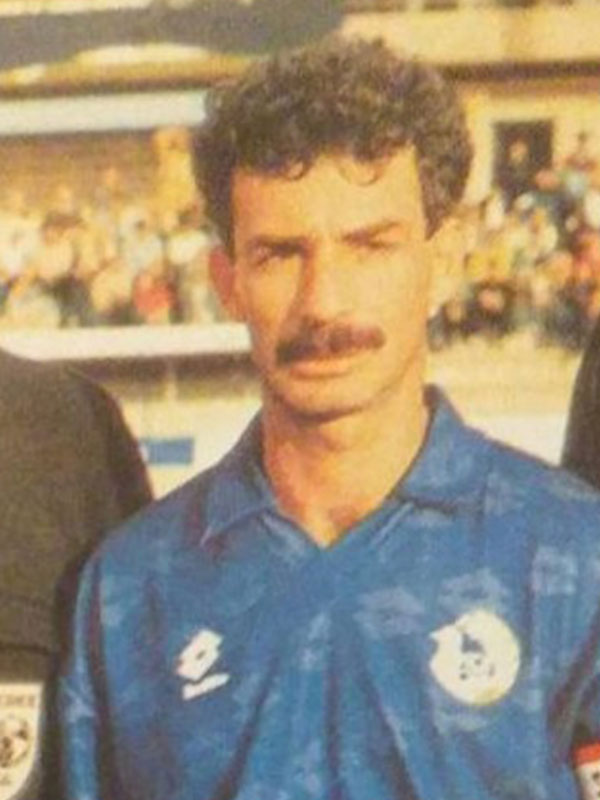

Pambos Pittas (1991 - 1993)

“Our biggest issue was the forced ‘bonding’ of players to the clubs they signed with as children. Players were essentially held hostage by the clubs, often without even having contracts. After persistent and determined efforts, we managed to reach an agreement with the CFA that allowed players to change clubs at the age of 32.

During that period, PASP’s membership grew significantly, which greatly strengthened our influence, as our voice became much louder.”

Giorgos Constantinou (1993 - 1994)

“In November 1993, I assumed the presidency of PASP through an interesting turn of events. When we, as members of the Board of Directors, met to form the new board, I tied in votes for the position of president with Loukas Hadjiloukas, who later withdrew his candidacy, allowing me to take on the role of President. I resigned from this position after about six months.

At that time, the board included former president Pambos Pittas and future president Pampis Andreou, who served as vice president. During that period, both when I was president and earlier when I was a board member under Pambos Pittas’ presidency, our discussions and negotiations with the CFA continued, primarily focusing on securing players’ freedom of movement. The Cyprus Sports Organization (CSO) played a significant mediating role in those discussions and was much more actively involved in Cypriot football at the time.”

Pambis Andreou (1994 - 2003)

“PASP had finally established itself in the minds of footballers after years of effort. One of our first actions was to engage with the CFA to address the issue of player freedom after reaching a certain age. In 1996, we managed to secure freedom of movement at age 30, which caused quite a stir. It was implemented in 1997, and those who were 30 years old were free to leave their clubs.

Then came the Bosman ruling, which changed everything, and by 1999 free contracts were introduced. The biggest challenges players faced at the time were financial struggles and the lack of medical coverage and insurance. Clubs refused to support us on these matters, while we were also clashing with club presidents over the number of foreign players. We demanded that the number of foreign players remain at two rather than being increased to three.

During that period, relationships with FIFPRO had already been established, and PASP was receiving financial support from them. We also had an excellent relationship with the Greek players’ association (PSAP) and its president Antonis Antoniadis. Another milestone of the era was the inclusion of Second Division players within the ranks of PASP.”

Costas Malekkos (2003 - 2008)

“When we took over, our first priority was to strengthen our relationship with FIFPRO. We attended FIFPRO conferences, demonstrated that we were present and strong, and secured a solid connection with them. Our next step was to acquire our own offices, and we made a major investment by purchasing the building where the Association is currently based. We designed a logo, hired a secretary, and brought players closer to the Association through regular engagement with them.

We also reached an agreement with ANT1 for the annual awards, which they organized under our authorization. The arrival of numerous foreign players completely changed the landscape of Cypriot football. We held multiple meetings with the CFA, aiming to protect Cypriot players. However, their hands were tied, as were ours, and thus the uncontrolled influx of foreign players began with Cyprus’ accession to the European Union. Still, we could have implemented measures back then—such as the current system of fines for teams that fail to include Cypriot players in their starting lineup.”

Spyros Neophytides (2008 - 2018)

“There were many significant milestones during my tenure as president of the Board of Directors. First was the full repayment of the Association’s privately owned offices. In 2009, PASP hosted the FIFPRO European Congress in Limassol for the first time in Cyprus.

Another major milestone was the electoral process in 2014 that secured my election to the FIFPRO Board of Directors. I can confidently say it was one of the most difficult and nerve-wracking elections in history. I had to win the position twice due to an appeal from Portugal. It was a tremendous achievement to go from being one step away from expulsion from FIFPRO, spending five years under supervision, to ultimately earning trust and being elected to the board.

Finally, in 2015, after months of discussions and negotiations between PASP and the CFA, guided by FIFPRO, the Cyprus Football Association adopted the Standard Player Contract for professional male and female footballers.”

Giorgios Merkis (2018 - σήμερα)

1987

1997

2004

2005

2009

2014

2015

2017